Governance

This second article on the Aged Care Royal Commission[1] discusses the governance structures for the aged care sector canvassed in the Commission’s report.

The Commissioners differed on the issue.

Commissioner Briggs’ model was a ‘stewardship’ model vesting governance responsibilities with with the Federal Department of Health and Aged Care:

One presumes that a ‘stewardship’ model is one in which government acts as an active and ethical trustee of public health, dedicated to developing the collective health commons’[2].

Commissioner Briggs thought:

In our Westminster system of government, responsibility for deciding on national values, interests and priorities rests with the elected government, through its Cabinet processes. Decisions about aged care involve social values and preferences. These are matters for collective consideration by the Cabinet and Parliament, as representatives of the people. They are not matters for arms-length agencies independent of the Government to determine.

The Australian Government, working through a Minister and a responsible Department of State, can act in ways that no other body working in isolation can match. Large, dispersed systems like aged care need this cut-through government capability to motivate and direct change. Without it, I fear that little will happen.[4]

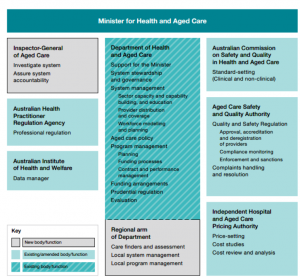

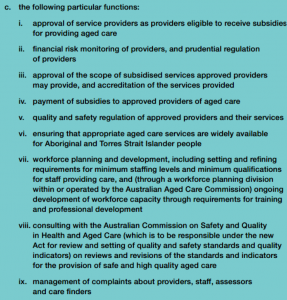

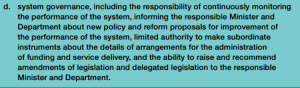

Commissioner Pagone has proposes the establishment of a specialist Australian Aged Care Commission which will ‘act as an independent champion for high quality and safe care rather than have decisions made by the very people who must compromise between competing government and political priorities’, discharging these functions:

as well as:

This model looks pretty much like the Australian Securities and Investment Commission[3] (ASIC) structure.

Commissioner Pagone thought:

What Australians need for those in, and affected by, is an independent champion for high quality and safe care than to have decisions made by the very people who must compromise between competing government and political priorities.

The independence of a Commission will enable it to put forceful arguments to secure what is needed to ensure that older people get the high quality care they need rather than needing to justify, and at times obscure, compromises between conficting or competing demands.

The same cannot be achieved by requiring a Minister to make aged care a priority. It is instructive to look at the 1997–98 Annual Report of the Australian Department of Health and Family Services. Even then, its vision was expressed in terms that I have found to be lacking in the aged care system that has required this Royal Commission. (sic) Many of the recommendations that we make to improve the system were expressed in the ‘vision and mission’ of the Department at that time. Stating them again will not deliver them: a separate, focussed and, crucially, independent champion has more chance in doing so.

Internal structural changes within a department are also less likely to produce results than an independent Commission with the sole task of advancing the high quality care of older people…….[5]

A specialist body may attract people experienced in, and dedicated to, delivering quality aged care and developing aged care policies.

It is our experience that governments treat public sector administrative ability as a generic skill that can be transferred from department to department. There is no sign of any change to this view.

As recently as 2019, senior Australian Public Service officers were argued that mobility between departments can ‘foster diversity of thinking, contestability of ideas an assist in capability development – lifting the overall capability of the APS, not just the individual.’[6]

And so, the more talented officers move around to seek promotion.

This is something that Commissioner Briggs seems to concede, when she says:

The reforms Commissioner Pagone and I propose represent sweeping changes to the delivery of aged care services and supports. To ensure that the reforms are implemented in the most effective and rapid way, there is a need for a joined-up approach across all the parts of the Australian Government that infuence the quality and safety of aged care. We have seen too many examples where government responses to meeting aged care needs have been fragmented and have failed to achieve the objectives sought because they were pursued in isolation.

Notwithstanding this, I have been disappointed during our inquiry by what appeared to be a considerable loss of corporate knowledge and aged care expertise in the Australian Department of Health arising from past organisational changes. We need some stability in institutional structures and continuity of expertise to carry the reforms forward. [7] (emphasis added)

However, it is unlikely that an independent Aged Care Commission would act as both system regulator and ‘champion’ of aged care recipients.

Irrespective of policy sector, regulators generally don’t tend to ‘champion’ those they serve as that usually means having to acknowledge shortcomings and errors. This seldom happens in practice.

The ‘championing’ role should probably fall to the proposed Inspector-General of Aged Care that is to ‘investigate, monitor and report on the administration and governance of the aged care system’.[8]

It will be interesting to see how a ‘rights based’ aged care system will be designed.

[1] https://agedcare.royalcommission.gov.au/

[2] https://www.who.int/bulletin/archives/78(6)732.pdf

[3] https://www.transparency.gov.au/annual-reports/australian-securities-and-investments-commission/reporting-year/2018-2019-3

[4] Pages 60-61 Volume 3A

[5] Pages 42-43 Volume 3A

[6] https://www.themandarin.com.au/103216-aps-leaders-want-more-staff-mobility-but-the-uk-civil-service-demonstrates-the-downsides/

[7] Page 65, volume 3A

[8] Recommendation 12, page 80 Volume 3A